1. A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments (1997) by David Foster Wallace

I have yet to read Infinite Jest (it is on my bucket list), but I enjoyed this collection of DFW’s long nonfiction essays, maybe even more than his short fiction. They are absolutely genius—not just in their content but in the craftsmanship of the prose on a sentence level. I read a couple of these essays several years ago but struggled with Wallace’s complicated syntax. Between the page-long sentences, invented words and acronyms, and multi-paged footnotes, you practically need a map to read a David Foster Wallace book. With my reading comprehension having expanded since then, I can now better understand and appreciate the complexity of his prose. Few writers could string words together better than DFW (RIP). The essays in this collection include:

- “Derivative Sport in Tornado Alley” – About DFW’s childhood in the American midwest playing competitive junior tennis. His tennis game was a lot like my own—just keep the ball in play and wait for your opponent to make a mistake.

- “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction” – A brilliant essay about how television (and technology in general) changes fiction writing. I wrote an entire post about this eerily prophetic essay, arguing that DFW’s critiques of TV culture are even more relevant today with the rise of the internet and social media.

- “Getting Away from Already Being Pretty Much Away from It All” – A detailed travelogue of the 1993 Illinois State Fair, cataloging carnies and American culture in the early 90s. It is fascinating now to see what has changed and what hasn’t.

- “Greatly Exaggerated” – A short essay about the “Death of the Author” and the interpretation of literature.

- “David Lynch Keeps His Head” – At once a profile of director David Lynch, a review of Lost Highway, a behind-the-scenes look at the making of the movie, and a philosophical examination of the medium of film itself—and an exemplary execution of each. I was already a fan of Lynch, but DFW’s examination of his films makes me appreciate them even more.

- “Tennis Player Michael Joyce’s Professional Artistry as a Paradigm of Certain Stuff about Choice, Freedom, Discipline, Joy, Grotesquerie, and Human Completeness” – DFW could make a long essay about a 1990s-era mid-tier tennis player I’d never heard of competing against even lesser-known players in qualifying matches for a tennis tournament in Canada utterly fascinating. (DFW also makes me write longer and more complex sentences.)

- “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again” – An account of Wallace’s experience traveling alone on a 7-night luxury cruise to the Caribbean. He brilliantly captures the absurdity of cruises in hilarious detail.

2. The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human (2012) by Jonathan Gottschall

This is a fascinating book about the science, psychology, philosophy, and history of storytelling. It takes an evolutionary psychology perspective and comes to many of the same conclusions that I did intuitively in my blog post “The Purpose of Stories.” Gottschall argues that Homo Sapiens could more accurately be called “Homo fictus” or fiction man. “The human mind was shaped for story, so that it could be shaped by story.”

It was gratifying to see him support many of my theories and back them up with rigorous scientific references. “Good fiction tells intensely truthful lies.” Humans would not be human without fictional stories. Stories are how we learn, pass on knowledge, and empathize with others. We even dream stories when we sleep.

All religions and political myths are delivered through a story. Stories mold moral behavior. Conspiracy theories are often an attempt to make sense of the incomprehensibly complex reality around us through a more simplified story.

Stories can bind society together but also tear it apart. Our memories are stories we tell ourselves, and our sense of self is narratively driven: everyone is the hero in the story that is their life.

3. The Fourth Turning: An American Prophecy — What the Cycles of History Tell Us About America’s Next Rendezvous with Destiny (1996) by William Strauss & Neil Howe

The Fourth Turning is a fascinating study of cyclical history, or the idea that history is not linear but follows a natural cycle that repeats over time. Therefore by studying the cycles of history you can better understand the present and predict the future. This may sound like pseudoscience to some, but many of the predictions made in this book written over 25 years ago have already come true.

Civilizations have seasons just like nature: from spring (when the civilization is born) to summer (the high point) to fall (the decline) to winter (the low point), upon which they return to spring again. This cycle is seen throughout history and all civilizations across the world throughout time. History repeats but it is not a circle, it is a spiral. After each cycle, technology advances and humanity’s collective knowledge grows, so when civilization collapses society can potentially rebound quicker, to a higher rung on the civilizational spiral.

The second half of the book focuses on specific American generations: G.I., Silent, Boomers, Gen-X, and Millennials. These generations of humans follow similar cycles as civilizations as a whole—one influences the other. “History shapes generations, and generations shape history.” As generations come of age they adopt different characteristics (Prophet, Nomad, Hero, or Artist) depending on the current part of the cycle. The state of the civilizational cycle that the generation is born into leads to certain cultural traits, dispositions, and worldviews for members of that generation. Obviously there are exceptions—these are not hard and fast rules—but you can see these general cycles repeat throughout history. By studying the cycles of history, you can recognize where we are now and therefore predict where we might be heading in the future. Then you can prepare for a potential winter. The “fourth turning” refers to a Black Swan-like event that leads to winter (such as a war or economic depression).

The cyclical history theory doesn’t negate the ability of individuals to make a difference, but it does limit their potential. A great individual such as Julius Caesar in Rome can arise and have a massive impact on the course of history; however, a Caesar figure can only rise to power during a particular part of the civilizational cycle. Only after a fourth turning is there the opportunity for such an individual to rise to power. If the cyclical theory of history is correct, and we are indeed approaching (or amidst) a fourth turning, then we should soon expect an individual to rise to power who will have a massive effect on future history.

4. Chuck Klosterman IV: A Decade of Curious People and Dangerous Ideas (2006) by Chuck Klosterman

A collection of essays by Klosterman, mostly from his magazine writing career for Esquire, Spin, and Grantland. Some of the pieces I read before, but they were worth revisiting years later to see in a different light. He covers so many different topics and always has a uniquely interesting perspective. Klosterman is the master of dumbing down smart things and smarting up dumb things. He is actually similar to David Foster Wallace, except he’s less depressed with a slightly lower IQ (which may be related).

5. The Screwtape Letters (1942) by C.S. Lewis

This is technically fiction, but it feels more like nonfiction—philosophical/theological essays in the frame of letters between fictional characters. It is composed of a series of satirical letters from servants of the devil conspiring how to corrupt humanity and ensure we join them in Hell, which includes doing many of the things many humans currently do. Lewis conveys great wisdom as valuable now as ever.

6. Man and Technics: A Contribution to a Philosophy of Life (1931) by Oswald Spengler

This was a short appetizer of historian Oswald Spengler’s work before I plan to dive into his magnum opus, Decline of the West. Man and Technics is about how technology and humanity are inextricably intertwined. Humans are the species that invented technology, and we evolved in conjunction with it and continue to do so today. As opposed to the storytelling animal, Spengler would argue we are the technological animal. But modern technology is removing our humanity as more and more technology makes humans obsolete. Some passages were striking by how directly they related to my book, Work for Idle Hands.

Spengler also touches on his cycles of history theory which he expands on in Decline of the West (no doubt an inspiration for The Fourth Turning), about how technology will lead to the fall of Western civilization—and there is nothing that can be done to stop it. I would hope Spengler is wrong about that, but unfortunately his predictions so far seem to be right on track.

7. Welcome to Hell (2021) by “Bad” Billy Pratt

“Bad” Billy Pratt is like Chuck Klosterman meets Delicious Tacos. This is a collection of essays, mostly about his experiences with online dating in the modern age, but infused with lots of pop culture references and critiques of movies and music. Plus writing about writing.

8. Myths to Live By (1972) by Joseph Campbell

I watched and loved Joseph Campbell’s PBS special, The Power of Myth, but this was the first book of his I read. It is a collection of essays, though it is actually a collection of transcripts from various lectures he gave, so it is not especially well-written. But the ideas are what matters. He brings his mythopoetic perspective to topics such as the moon landing, schizophrenia, LSD, East vs. West, Zen, war, love, art, science, religious rites, and the evolution of mankind.

9. Decline and Fall: The End of Empire and the Future of Democracy in 21st Century America (2014) by John Michael Greer

Throughout all of human history, every empire has fallen, due to various internal problems that arise from pursuing and maintaining imperial power. After World War 2, the US became the global empire, and like all empires, they received massive rewards from their global domination thanks to cheap money and cheap energy. But eventually that cheap money and energy runs out and the massive weight from maintaining a massive empire bears down, as it has on all empires. The US is now in decline and doomed for collapse—not necessarily as a country, but as a global empire. And the US ceasing to be a global empire may be better for both the US and the globe.

10. Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones (2018) by James Clear

This is a good self-help book on how to use habits to improve your life and productivity, both by encouraging good habits and discouraging bad ones. A lot of it seems pretty obvious, though we often ignore the obvious and get stuck in poor habits. I certainly could have benefited this book earlier in my life. But instead I learned many of the lessons from Atomic Habits the hard way: through trial and error. After years of suffering, I changed my health with better eating habits and exercise habits, my productivity with better reading and writing habits, and avoiding the time drains of bad habits such as too much Twitter and social media. So now I feel in a pretty good place health-wise and productivity-wise, in that I have mostly cultivated good habits and avoid the bad ones. However, there is always room for improvement around the edges. While this book was not an enormous help to me at this point in my life, I would certainly recommend it to my younger self and anyone else being hampered by bad habits and in need of better ones to improve any facet of their life be it diet, health, career, productivity, etc.

Honorable Mentions:

Nightmareland: Travels at the Borders of Sleep, Dreams, and Wakefulness (2019) by Lex “Lonehood” Nover

This is another book I was drawn to by the cover. Unfortunately, it was merely good but not great. It’s about the many weird and horrific things that happen when we sleep including: sleep paralysis, nightmares, sleeptalking, sleepwalking, hypnagogia, psychic attacks, alien encounters, and lucid dreaming. It includes many anecdotes and true stories, such as people who committed murders while sleepwalking, though some of the more outlandish claims you have to take with a grain of salt because there is no evidence other than the person’s word.

A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather Than Nothing (2012) by Lawrence M. Krauss

The single question that has both fascinated and confounded me most my entire life is: Why is there something rather than nothing? It seems like a paradox, impossible to answer. The religious would say because “God,” and the atheists would say because “a quantum fluctuation,” but both God and quantum fluctuations are still something. Why do they exist? Krauss, a physicist, takes the atheistic materialist approach to attempt to answer the question through science alone, dismissing philosophy as a waste of time. He does a decent job of laying out the physics in a comprehensible way, but his ultimate “answers” are lacking. He basically explains how “nothing” is unstable and quantum fluctuations will cause “something” to arise, namely a Big Bang with inflation and expansion into a universe. He admits in his introduction that philosophers will object that the preexisting conditions that cause the quantum fluctuation, including the natural laws of physics, are still “something”, but he does not attempt to provide an answer for where they came from. Ultimately this book was a fine enough explanation of how our universe came into being, but it fails to answer the fundamental question of why there is something rather than nothing.

Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine (2018) by Alan Lightman

This book is a series of poetic essays on science, philosophy, religion, and the relation of all three of those domains. Though he is a physicist, Lightman is less of a dogmatic reductional materialist as Lawrence Krauss, and humbly admits there are certain questions (such as why is there something rather than nothing) that lie outside the realm of science.

Self-Editing for Fiction Writers: How to Edit Yourself Into Print (2004) by Renni Browne & Dave King

A helpful book for fiction writers to improve their prose through self-editing—though take all writing advice with a grain of salt. The writers said it best in this book: “Literature is not so much correct (or incorrect) as it is effective (or ineffective).” Browne and King provide some useful tips to make one’s writing more effective.

One Simple Idea: How Positive Thinking Reshaped Modern Life (2014) by Mitch Horowitz

This is not a self-help book, but a history book about self-help books, positive thought, and the New Age movement. It’s an interesting topic but the book is mostly a dry history covering the biographies of the people involved in these movements mostly in America, from Christian Science to Dale Carnegie to Tony Robbins and many more. The final chapter, “Does it actually work,” was much more interesting, and I would have preferred more of that.

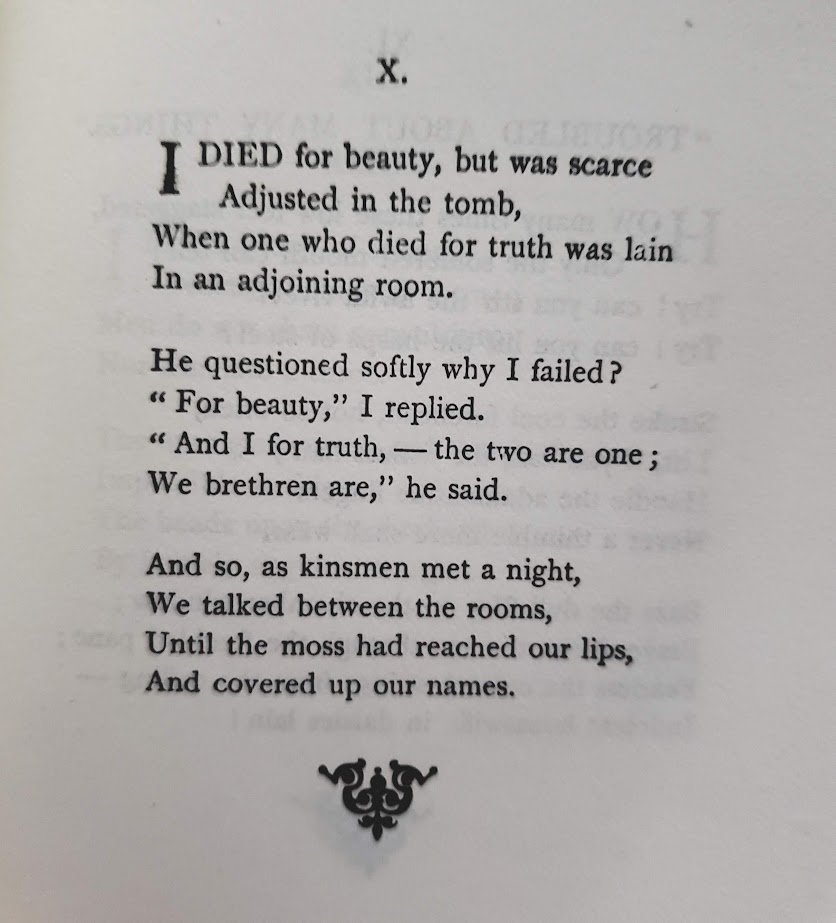

The Top 500 Poems edited by William Harmon, The New Oxford Book of American Verse by Richard Ellmann, & Favorite Poems of Emily Dickinson

I was never a huge reader of poetry, though I have written a few poems myself (and not just Christmas parodies). I’d of course read some famous poets in school, such as Robert Frost, and I always enjoyed Edgar Allan Poe’s poems in particular—still do. Call me simple, but I prefer rhythmical and rhyming poems and struggle to get into modern free verse. I’ve been trying to read more poems this past year with my new ritual of reading one poem per day in the morning. I have several large collections of greatest poems that I’ve been reading from, plus a small book, Favorite Poems of Emily Dickinson, who might be my favorite poet of all. (The Art of Darkness podcast did a good episode on her.)

When considering which list to put these books on, fiction or nonfiction, it made me realize poetry is a category unto itself. A poem is neither fiction nor nonfiction because it is both fiction and nonfiction. (I ended up putting the poetry books on this list because my fiction list was already much longer.)

The King James Version of The Bible

I started reading the King James Version of the Bible this year (I’m currently about a third of the way through the Old Testament) for several reasons. 1) I’ve never read the KJV, which many say is the best, most poetic translation and extremely influential on the history of Western literature. 2) I went to Catholic school and learned most of the stories from the Bible but have never read it straight through from beginning to end. And 3) I have never read the Bible as an adult. Figures such as Jonathan Pageau and Jordan Peterson have inspired me to take a deeper, more symbolic look at the stories in the Bible. Genesis is especially fascinating, full of symbolism that can be interpreted endlessly.

New Blogs & Substacks I started following:

- The Abbey of Misrule by Paul Kingsnorth

- The Double Dealer

- Fictions by P.C.M. Christ

- Man’s World Magazine

- MythoAmerica

- Peachy Keenan

- Trantor Publishing by Isaac Young

- Uncharted Territories with Tomas Pueyo

Plus Some Old Favorites:

- Astral Codex Ten by Scott Alexander

- Astral Flight Simulation

- The Carousel by Isaac Simpson

- Countere Magazine

- Default Wisdom by Katherine Dee

- Ecosophia by John Michael Greer

- Effluvia by God Disk

- The Egg And The Rock by Julian Gough

- From the New World by Brian Chau

- Gray Mirror by Curtis Yarvin

- The Intrinsic Perspective by Erik Hoel

- Living into the Dark by Matt Cardin

- Numb at the Lodge by Sam Kriss

- The Obelisk by The Bizarchives

- Other Life by Justin Murphy

- Overcoming Bias by Robin Hanson

- Pirate Wires by Mic Solana

- The Prism by Gurwinder

- shift sepulchre by ctrlcreep

- Teach Robots Love by Autumn Christian

- Time Zone Weird by Me

- The Total State by Auron MacIntyre

- Wait But Why by Tim Urban

- The Writings of T.R. Hudson

- Zero HP Lovecraft