One of the potential applications of AI text generators such as ChatGPT is creating a chatbot based on people who have died so that users can speak to those “people” after they are gone. This could be done with famous figures from history or personal loved ones. Such “grief tech,” as it is called, is already being created: HereAfter, You Only Virtual, Character.ai, and MindBank are just a few examples. There are currently apps where living users answer questions now to help create an AI chatbot clone of themselves that others can speak to after they die.

Theoretically, if a person has enough textual data to input into the model (from books, journals, social media posts, emails, and text messages), then the AI trained on that data can anticipate what that person is likely to say given any prompt (which is essentially how all LLMs work). The chatbot will learn to write in the style of the deceased person based on their personal data. Using continually updated data from the internet, the “deadbot” can comment on current events, making it seem as though the person is still alive. Users can learn what the deceased person would think about things that have happened in the world since they passed away. Or they can ask the chatbot all the questions they wish they had asked while the person was still alive. At least that is what the chatbot’s creators will claim their AI can do. But this is a false hope, a facade. AI cannot predict what a deceased human being would think or say years or decades later. You cannot create an accurate chatbot based on the data of the dead.

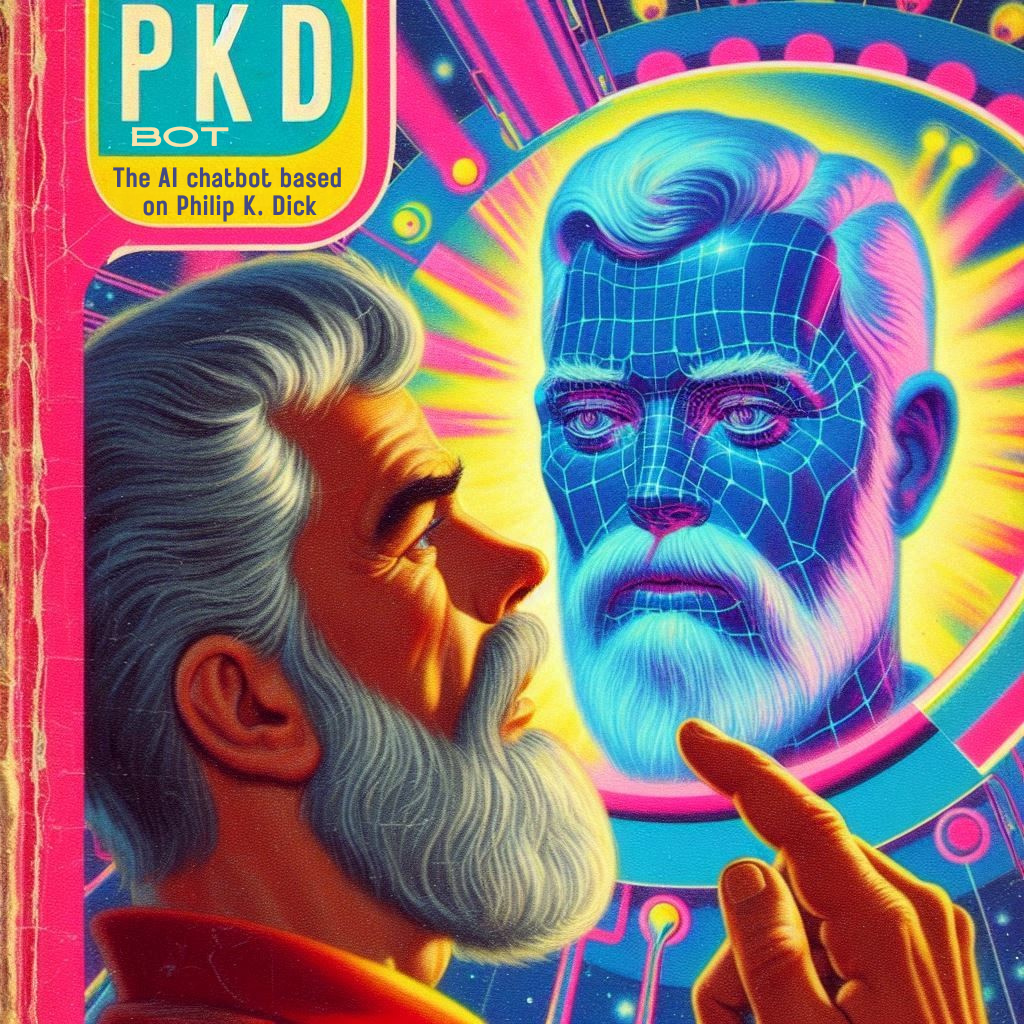

Consider a “PKD-bot” that is created based on the writings of Philip K. Dick, including his 44 novels, 121 short stories, plus all his essays, letters, and journals, including his 8,000 page Exegesis, in which he attempted to make sense of his “2-3-74” visionary religious experiences. Dick was a prolific writer, so there is a vast amount of data for his AI model to mine. A PKD-bot would conceivably be able to write in PKD’s voice about any given topic. Plus, considering PKD wrote explicitly about the future and robots, a PKD-bot would be especially useful for asking questions about the future, technology, and artificial intelligence. Whereas a chatbot based on the diary of your great-grandmother might not know what to say about the technological singularity.

This PKD-bot (and other dead person chatbots) may seem impressive, but PKD-bot is not PKD. You cannot use a Philip K. Dick chatbot to find out what Philip K. Dick would say or write about any given prompt, because PKD himself would say and write different things at different points of his life. Every human being is constantly changing—at least interesting humans are. Any given data from someone’s past is just a snapshot, a reflection of their thinking at that specific point in time. It would have been different earlier, and it will be different later. I am much the same.

Every seven years I am a different person, both literally and figuratively. Each cell in the human body is replaced every seven years, so physically I am composed of different cells. This may or may not be related to how my consciousness also changes over that same timespan. My ideologies and interests gradually shift as I learn more about the world. This should happen to anybody who continually reads and learns. Even my personality, which is often believed to be static, has changed over time to some degree. In 2016 I was an INFJ on the MBTI scale, but after taking the test again in 2020 I was an INTP. Such personality tests may be fickle, but I have certainly become more “Spock-like” over time—less emotional and more logical. To create an AI chatbot based on me would include data from my past that seems like a completely different person than I am now. It will include things I said but no longer agree with. I suspect the data of most other people would be the same.

“I must preface all my remarks by the qualifying admission that they do not necessarily constitute a permanent view. The seeker of truth for its own sake is chained to no conventional system, but always shapes his philosophical opinions upon what seems to him the best evidence at hand. Changes, therefore, are constantly possible; and occur whenever new or revalued evidence makes them logical.” — H.P. Lovecraft

It is absurd to have an AI based on a dead person’s data and ask them something like, “What is the meaning of life?” My answer would be different each decade of my life, but that doesn’t mean any answer was right or wrong. This applies to any subjective questions you might ask a deadbot. And almost all the questions people ask deadbots will be subjective, otherwise they could just look up the answer on Google. To have an AI chatbot give a single definitive answer to a subjective question is completely arbitrary. The deadbot of your father might say something that will make you think, I could see him saying something like that—but there are a thousand other responses that you could also see him saying as well. The question you should be asking yourself is: Who is choosing that single response?

Furthermore, this is all assuming the deadbots work as intended by accurately representing the person’s view, and aren’t being manipulated by algorithms or censored by the company that owns the AI, for whatever reason. That is a whole other can of worms, and why you should be even more skeptical of chatbots based on humans. The chatbot of your great-grandfather may be more politically correct than he actually was—and he may casually mention products and services that the corporation controlling the chatbot endorses.

Despite millennia of study, scientists and philosophers still cannot explain human consciousness: what it is, where it comes from, or how it works. Deadbots operate under the false premise that consciousness is merely based on data—take a person’s brain data and you can reproduce their consciousness. This would negate free will, in the respect that humans are simply algorithms responding to data. But as deadbot users will come to see, this is not the case.

Data certainly plays a role in consciousness. New brain data, or knowledge I encounter, alters my consciousness (my thoughts and feelings). But there is a mystery to consciousness beyond mere inputs of data. I do not condone anything the future AI chatbot based on my data says—because I do not condone everything I myself said in the past. And a dozen years from now, I might even reject everything I’ve said in this very essay. I already disagree with much of the content in previous posts on this blog, though I believed it at the time. Which reiterates my central thesis: that consciousness is not static; it is ever-evolving.

AI chatbots based on the deceased might help some people through difficult times of grieving, or they could be fun as a piece of entertainment, but take grief tech with a grain of salt. You cannot expect anything a deadbot says to be what a person from the past actually thought—unless the person literally wrote about that topic. In which case, just read their own words, not some algorithm’s interpretation and extrapolation of them. Ask your loved ones the questions you want answered now while they’re still living, and write your personal answers to life’s deepest questions in your own words. That is the only way to ever know what a person truly thinks—though even then it will be fleeting, a single snapshot of consciousness in its constant evolution over time.